- Posted on

- Unique Submission Team

ADVANCED OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT: ASSIGNMENT

1. Role of Operations Management

Operations management is core business process that directly relates to the manufacturing of goods or services. However, the process of converting resources into finished products or services is extremely complex and instrumental to the success of the business.

Hence, operations management is undertaken to manage this task, which is to oversee and direct resource allocation and utilisation in manner where the company meets its goals and objectives. In other words, operations management helps configure company resources in an effective way, which delivers maximum value for both the firm and its customers.

While, operations management covers various functions within the firm, the common roles that it plays within a firm is measurement, planning, communication, resource allocation, monitoring, and analysis (Slack et al. 2010).

Measurement and monitoring–This involves the utilisation of strategic measuring tools to help assess various production functions. Through measurement key aspects of production like quality, quantity and specifications can be continuously measured. While, it also allows the firm the measure productivity of the workers and pick up inefficiencies within the system (Stevenson and Hojati, 2007).

Planning and scheduling –This involves assessing the firm’s current position within a market, and planning for changes to help position the firm more effectively in near future. Hence, an assessment on current skills and capabilities,to help develop or adopt new ones, is acommon example (Krajewskiet al. 1999).

Communication –Arguably, one of the biggest role played by operations management is communicating between various firm processes, departments or sections in order to ensure smooth function of the production process (Kleindorferet al. 2005).

Acquisition and resource allocation –Lastly, resource allocation, which involves the transformation of “inputs” like raw materials, human resources, information, equipment and technology into finished products or services (Pilkington and Meredith, 2009).

‘Product design’ is related to the selection of materials and features that is best suitable for the target audience. While, this may seem relatively straight forward, product design is highly complex and time consuming. This is because product design involves many activities such as:

- Carrying out marketing activities that help translate customer demands into the finished product design.

- Refining the existing product line by eliminating flaws or faults experienced by existing users.

- Refreshing old or creating new products that cater to new or trending customer demands.

- Defining quality standards and goals for existing and new products.

- Undertaking cost analysis to help ensure the company stays within its financial goals.

- Development and testing of prototype products or services.

- Documenting product specification to help meet industry standards.

(Hill and Hill, 2012).

Selection criteria: This type of operation system involves activities like marketing, production, quality control, accounting and design. In addition, product design is a vital operation system, as decisions made regarding the product’s design can alter manufacturing capacity, requirements, speed and costs to a significant extent.

Hence, product design must be undertaken keeping in mind costs, material availability, function, reliability, company goals, quality standards, market demands and customer satisfaction (Fugateet al. 2009).

Limitation:That being said, budget limitations, innovation, creativity, technology, narrowed customer segments and product price can severe limit product design.

According to Barnes(2008), ‘process design’ involves sequence of operations that help the product meet its specifications. In other words, this system specifies machines, equipment and labour required for manufacturing the specific product. This is determined by factors like (a) product nature, (b) raw materials needed, (c) product quantity and (d) existing layout of the production plant.

Selection criteria:

- Product characteristics

- Target output volume

- Availability of machines

- Current workforce

- Cost of manufacturing

- Selection of either labour-intensive or capital-intensive manufacturing

- Deciding what parts to purchase and manufacture

- Efficient and economical material handling

(Seideret al. 2009)

Limitation: Firstly, process design will be limited to the type of machines and skills available to production. Secondly, existing machinery may be suitable for general-purpose use only; hence, producing complex or unique features or designs may become impossible.

‘Process strategy’ is best described as the approach towards process selection, where the primary goal is to convert resources into a finished product while attempting to fulfil customer requirements, product specification and cost targets (Leonard, 2011).

Selection criteria: Selection of process strategy can be classified into three categories; namely, process focus, repetitive focus and product focus.Process focus refers to the strategy where specialisation in each department allows for specific jobs like grinding, painting, welding etc.

While, repetitive focus relates to a strategy wherethe focus is to create modular parts in a repetitive actions, for example, the production of plastic bottles using injection moulding. Lastly, if the process strategy is product focus, then high volumes of a low variety product are created in a long assembly or product line; for example, light bulbs (Pilkington and Meredith, 2009).

Limitation: Process strategy requires significant research and considerations before deciding upon a specific focus. As a result, changing focus midway can become extremely difficult without incurring huge costs.

2.4 Operations management processes

Projects – Projects involve the creation of a single output or product over a specific period.For example, the construction of large products like infrastructure, buildings, stadiums, roads etc. Unlike other types of processes, projects end as soon the end-output is achieved.

While, only a single deliverable is the project’s ultimate goal, the process can be modified in a manner where it can be reused for producing multiple outputs over time(Stuartet al.2002).

Jobbing –Jobbing processes are also referred to as “job shops”, where the primary focus is to created different products in small batches. Each batch of products are customised to meet individual customer or client requirements, which results in different processing times and costs.

For example, a bakery specialised in wedding cakes, will bake and decorate cakes based on the marriage requirements like size, flavour, icing, style etc. Another example of a jobbing process is an online company that creates customised webpages for its customers (Desai, 2008).

Batching –Batching are similar to job shops in the sense they also periodically create batches of the same product; however, unlike jobbing, batch shops produce identical products, which are not customised. As a result, each batch or set of products follow the same creation or process flow.

For example, a bakery that producesseveral varieties of chocolate biscuits will only bake those varieties based on predefined production processes; rather than custom orders. Hence, in batching, the buyer or client can only select the type of variety available and the quantity(Potts andKovalyov, 2000).

Mass or Assembly Lines –In this type of process, a product is assembled as it moves forward on a flow line. Assembly lines possess individual workstations that specialise in a specific action, process or part. As the product moves through each workstation, the product line halts temporarily and only moves when the concerned workstation has completed its tasks.

Using this method, products can be assembled in mass numbers in efficient and cost effective manner. For example, a car manufacturing plant, which assembles each part of the car, by collecting parts from each departments or stations like welding, painting, engine, chassis etc (Slacket al. 2010).

Continuous flow – in this operational process, products are continuously being produced on a 24×7 basis, through automation. For example, an electric generation plant that runs continuously through automated processes (SchmennerandSwink, 1998).

3. Strategic planning tools and techniques

Situational analysis is technique used to map the current external and internal situation or current scenario. The external situation is influenced by macro environmental factors like political stability and economy, while the internal situation is affected by process occurring within the company like HRM or IT.

Therefore, businesses are required to analyse their external and internal business environment in order to undertake effective strategic planning. Two strategic tools used for situational analysis are PEST and SWOT. PEST or PESTLE is used to study external factors like political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental. These external factors may influence the business in several ways; hence, must be monitored regularly.

SWOT

The SWOT tool helps assess internal factors by determining the company’s strengths and weaknesses. It also helps draw a picture of potential opportunities and threats currently present within the market of operation (Teece, 2010). Using the SWOT tool a firm can on focus on its strengths, while minimising its weaknesses. An example of a SWOT conducted on an automobile industry is demonstrated in Table 1 below.

Strengths ü Low cost manufacturing ü High product volume ü Strong revenue generation

| Weaknesses ü Limited markets ü Lack of R&D |

Opportunities ü Product diversification

| Threats ü Electric Cars |

Table 1: Sample SWOT

(Created by Author)

Based on the Swot analysis,the firm can utilise its strong revenues to overcome its two weaknesses. Revenues can be used to expand into foreign markets, while investing in R&D can results in newer products, which helps diversify its product offering. Lastly, the threat of electric cars can be minimised by introducing hybrid vehicles, which can be developed through R&D (Pickton and Wright, 1998).

Managing Change:

If an organisation were operating while emitting 10 tons of CO2 per hour from its factories, changes in emission regulations that limit emissions to 5 tons of CO2/hour would make operations illegal. In such situations, the company must alter or change their manufacturing process in order to meet new emission regulations. In this regard, upgrading machinery, reducing wasted energy and incorporating renewable energy is a solution.

Analysis the company’s product-market portfolio involves the following processes (Kraus et al. 2006):

- Current product status: this involves analysing the current products operating within current markets, by profitability, suitability and lifecycle.

- Strategy identification: Upon product analysis, a suitable strategy to improve weak products and maintain strong ones is needed.

Managing Change:

As markets weaken or strengthen changes are needed in the product-market portfolio. However, in order to accommodate any such changes the following considerations must be taken into account. Firstly, the proposed changes must be inclined with the company’s mission and vision.

Secondly, secondly, determining the future of the core business. In other words, the need to determine if primary products are on a steady decline.In addition, determining if the business itself needs to diversify or enter new markets.Thirdly, changing according to current governmental policies and regulations. Fourthly, assessing if major changes will bring about new competitors within the market.

Fifthly, determining feasibility, suitability and financial viability of the proposed changes. Lastly, understanding if the changes cater to profitable supply/demand situations within the market.

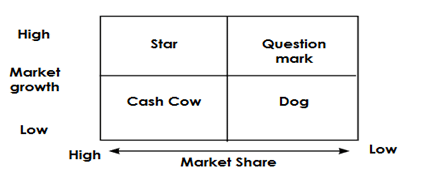

The BCG matrix is grid matrix that helps analyse products or product portfolio based on their market share and growth.

Figure 1: BCG Matrix

(Source:Ioanaet al. 2009)

This matrix is also referred to as the growth/share matrix and is primarily utilised to classify products into four categories. Hence, based on their performance, products or services may classified as either stars, cash cows, dogs or question marks.Starsare the ideal type of the products to have in the product portfolio, as they demonstrate high market growth along with high market share.

That being said, star products require large investments, which usually promise high ROI. Stars eventual lose their growth potential and become ‘cash cows’, which help generate large volumes of profits. Question mark products are those with an uncertain future, as their market share is low despite their high growth rate.

In due time, question marks could either fail and become dogs or end up becoming stars. The least preferable type of product within the BCG matrix is dogs, as they represent low market growth/share combinations. Dogs can be considered failed or failing products. Hence, the matrix proposes a strategy of converting question marks into stars, and stars in cash cows is the proposed (Bold, 2011).

Managing Change:

If products fall in the question mark category, the firm must select a suitable few, which has the best potential for becoming stars in the future and divest the remaining. While, investment must be continued for star products to help transform them into cash cows. No changes are needed in products that have already become cash cows.While, liquidation is most appropriate for products categorised as dogs.

4.1 Role of Supply Chain Management

According to Seuring and Muller(2008), SCM is the oversight of data, materials and finances across the supply chain within a firm or company. In a sense, this practice helps manage the flow of materials from supplier to end user or customer. Hence, SCM helps coordinate various functions within the supply chain to help deliver products in an efficient and time saving manner. The various roles SCM plays within a company be categories as:

- Purchasing: This involves acquiring raw materials or procuring parts for the production process. This ensures that raw materials and all necessary items needed to manufacture the finished product are always present in stock (Ballou, 2007).

- Transportation: SCM also handles inbound transportation of goods into warehouses or production facilities. Likewise, goods leaving the storehouses or factories are managed by Supply Chain Management activities (Christopher, 2016).

- Quality Control: Through various feedback and data collection processes, the quality of products being manufactured is continuously been checked. More importantly, SCM strictly monitors and maintains industry standards and company standards on material handling, processing and shipping of products (Carter and Rogers, 2008).

- Demand/Supply planning: The demand of products within a market may fluctuate due to popularity or availability. It is SCM’s role to ensure the demand of the company’s products are being met, essentially preventing undesirable circumstances like illegal stocking or shortages.

- Handling and Storage: Once SCM procures materials, it arrives at the company’s various inventories or warehouses. Supply Chain Management then determines how those materials are received, handled and stored (Ballou, 2007).

- Inventory Control: Arguably, one of SCM’s most important role within the Company is to manage the inventory. SCM keep track and monitors all products entering and existing the inventory. If production requirements change, SCM issues instructions to accommodate that change. For example, in peak production season, SCM helps maintain minimum stock levels, so that production does not come to a halt (Stadtler, 2015).

- Order Processing and distribution: Once a customer or client makes an order, the SCM processes the payment and issues instructions for shipping to a given address. SCM may incorporate the following steps in order to accomplish this- First, receive orders and process payments.

Second, record transaction details like price and quantity within the company ledger. Third, issue pickup details to the warehouse. Fourth, issue delivery information to transportation department. Fifthly, track shipment until it arrives at the destination. Lastly, collect customer acknowledgement of having received the shipment (Liet al. 2006).

- Customer service: Upon arrival or while using the product, the customer may face difficulties or problems with the product. This could either be faults with the product itself or customer’s lack of understanding regarding its usage.

In either scenario, the customer contacts the Company to complain regarding the issue. SCM manages these complaints and ensures that issues are resolved in the shortest period possible. If a product is malfunctioning or has a production fault, the SCM receives the faulty product, notifies the respective department and issues a replacement. Hence, SCM plays a vital role in customer service with regard to processing returns or repairing faulty products (Christopher, 2016).

4.2 Challenges

- Customer Service:One of the key functions of SCM is to manage customer service, by ensuring that product quantity and quality is delivered on time to customers. Once a product is sold, after sales support complicates the supply chain. Customers may send back the product for faults, defects or broken items. When this occurs, the returning product requires additional resources, putting a strain on logistics and transportation.

In addition, since, customer service often involves servicing or repairing products, several steps must be followed in order to effectively deliver the product back to the customer. Hence, customer services complicate the supply chain, making it even more difficult for SCM to operate effectively.

- Cost Control:Operational costs are continuously on the rise, primarily due to a price increase of power costs, human capital, maintenance and raw materials.Hence, it is a massive challenge for SCM to carry out its activities while managing the rising costs.

- Planning:SCM being a multifaceted function requires continues monitoring and assessments, in order for its activities to stay efficient. Hence, planning activities must be undertaken periodically to help the organisation adapt to market changes. Due to this uncertainty, carrying our risk management within the supply chain is equally challenging.

- Relationship management:In order to possess an effective and competitive supply chain, cooperation and standardisation is required. This can only be achieved if suppliers and other key stakeholders possess a strong relationship with the firm. Hence, the SCM faces a constant struggle to keep relationships strong and productive.

(Stadtler, 2005).

5. Performance Measurement and Models

KPI or Key performance indicators are quantifiable measures used to assess performance over time. KPI are vital in determining strategic progress, with regard to meeting goals and objectives. In addition, KPI can also be utilised to measure a company’s performance within a market segment or industry, by comparing it with other competitors.

Usually, KPIs are categorised as non-financial KPIs and financial KPIs. First, Financial KPIs, as the name suggests involves the measurement of finances, primarily profit margins, assets, net profits and revenue. Second,non-financial KPIs related to non-financial measures like relationship with suppliers, customer satisfaction, employee turnover, brand loyalty etc (Bauer, 2004).

Performance managementwithin an organisation can be undertaken at various levels. These are process level, people level and product level.At the process level, KPI are used to assess performance based on efficiency, productivity, costs and speed. This allows the company to pick out processes that are consuming too much resources or cause repetitive delays in the production.

While, at the people level, KPI likeproductivity, target fulfilment, accuracy and ethics may be used to measure performance. Performance management at the people level allows the organisation to pick out star employees and reward them adequately, while providing a scope of improvement for those who exhibit lack of productivity or efficiency. Last, performance management at the product level. This involves the use of KPI like production costs, market competition, customer satisfaction, profits and long-term sustainability (Perrini and Tencati, 2006).

Measurement Tools and techniques

- Productivity Index: This tool utilises the simple equation of P=O/T, where P = productivity, O = output and I = Input. The primary aim of the index is to express a ratio between an output and an input. The simplicity of the equation means that it can be used to measure various processes, practices and even people within a company.

- However, this basic tool is not accurate as external factors, which may influence productivity like skills or equipment are not considered. That being said, there are several productivity indices available for the organisation to make more accurate assumptions; for example, employee-hour output, value of outputted goods-man hours used and added value-labour costs ratios (Bichou, 2006).

- 360-degree feedback:This technique utilises anonymous reporting and data collection techniques to help gain an unbiased report regarding employees, practices, processes and products. 360-degree feedback is generally collected from those who interact the most with a specific product, process or even an employee.

The primary purpose is to generate a broad understanding of product/service by collecting information from various sources like vendors, employees, clients and even customers (Lepsinger and Lucia, 2009).

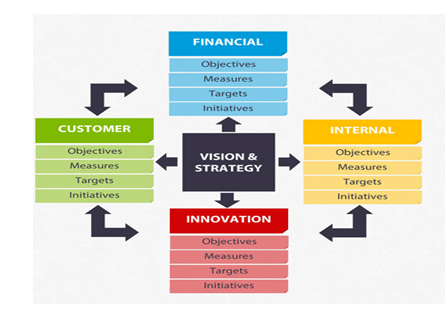

- Balanced Scorecard: The balanced scorecard is a strategic measurement tool that helps draw a “strategy map” of the entire business. It plays no role in developing strategies or directions; rather, only exist to paint a picture of the current business through data collection and benchmarking.

In this manner, the balanced scorecard helps collect performance measures from four different perspectives, which are financial, customer, internal process and innovation as seen in figure 2 The financial perspective assess “return on invested capital”, while the customer perspective seeks to collect data on “product delivery” and “customer loyalty”.

The internal process perspective primarily measures details like “process cycle time” and “process quality”. Lastly, the innovation perspective, which measures “employee skills” and “lagging/leading indicators”. Furthermore, each perspective lists the company’s objectives, measures used, targets set and initiatives undertaken (Huang, 2009).

The balance scorecard provide the firm with a set of advantages; these are:

- Overcoming challenges: Three major challenges namely strategy implementation, managing intangible assets and performance managementare addressed using the balanced scorecard. For example, the metrics provided by the balanced scorecard allows identification, evaluation and utilisation of assets within the firm.

- Broadened View: The four components of the balanced scorecard allows performance measures in growth/learning, internal process, financial and customer perspectives. This broadened view allows better decision making and strategic implementation.

- Structuring company strategy: As a strategic management tool, the balanced scorecard provides a logical and structured method to understanding the firm’s overall strategy. As a result, the information gathered can help leaders ensure that all areas within the firm have been addressed within the strategy.

- Communication: Another major advantage of this tool is that it allows enhanced communication with employees regarding the firm’s strategic direction, objectives and goals.

(Kaplan and Norton, 2006).

Figure 2: Balanced Scorecard

(Source: Huang, 2009)

Ballou, R.H., 2007. Business logistics/supply chain management: planning, organizing, and controlling the supply chain. Pearson Education India.

Barnes, D., 2008. Operations management: an international perspective. Cengage Learning EMEA.

Bauer, K., (2004). KPIs-The metrics that drive performance management. Information Management, 14(9), p.63.

Bichou, K., 2006. Review of port performance approaches and a supply chain framework to port performance benchmarking. Research in Transportation Economics, 17(1), pp.567-598.

Bold, E., 2011. Instruments and techniques used in the design and implementation of change management. Journal of Advanced Research in Management, 1(3), pp.5-13.

Carter, C.R. and Rogers, D.S., 2008. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: moving toward new theory. International journal of physical distribution & logistics management, 38(5), pp.360-387.

Christopher, M., 2016. Logistics & supply chain management. Pearson UK.

Desai, D. A. (2008). Improving productivity and profitability through Six Sigma: experience of a small-scale jobbing industry. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management, 3(3), pp.290-310.

Fugate, B.S., Stank, T.P. and Mentzer, J.T., 2009. Linking improved knowledge management to operational and organizational performance. Journal of Operations Management, 27(3), pp.247-264.

Hill, A. and Hill, T., 2012. Operations management. Palgrave Macmillan.

Huang, H.C., 2009. Designing a knowledge-based system for strategic planning: A balanced scorecard perspective. Expert Systems with Applications, 36(1), pp.209-218.

Ioana, A., Mirea, V. and Bălescu, C., 2009. Analysis of service quality management in the materials industry using the bcg matrix method. Amfiteatru Economic Review, 11(26), pp.270-276.

Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P., (2006). Alignment: Using the balanced scorecard to create corporate synergies. Harvard Business Press.

Kleindorfer, P.R., Singhal, K. and Wassenhove, L.N., 2005. Sustainable operations management. Production and operations management, 14(4), pp.482-492.

Krajewski, L.J., Ritzman, L.P. and Malhotra, M.K., 1999. Operations management. Singapore: Addison-Wesley.

Kraus, S., Harms, R. and Schwarz, E.J., 2006. Strategic planning in smaller enterprises–new empirical findings. Management Research News, 29(6), pp.334-344.

Leonard, D.A., 2011. Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. In Managing Knowledge Assets, Creativity And Innovation (pp. 11-27).

Lepsinger, R. and Lucia, A.D., 2009. The art and science of 360 degree feedback. John Wiley & Sons.

Li, S., Ragu-Nathan, B., Ragu-Nathan, T.S. and Rao, S.S., 2006. The impact of supply chain management practices on competitive advantage and organizational performance. Omega, 34(2), pp.107-124.

Perrini, F. and Tencati, A., 2006. Sustainability and stakeholder management: the need for new corporate performance evaluation and reporting systems. Business Strategy and the Environment, 15(5), pp.296-308.

Pickton, D.W. and Wright, S., (1998). What’s swot in strategic analysis?.Strategic change, 7(2), pp.101-109.

Pilkington, A. and Meredith, J., 2009. The evolution of the intellectual structure of operations management—1980–2006: A citation/co-citation analysis. Journal of Operations Management, 27(3), pp.185-202.

Potts, C. N. and Kovalyov, M. Y. (2000). Scheduling with batching: A review. European journal of operational research, 120(2), pp.228-249.

Schmenner, R. W.andSwink, M. L. (1998). On theory in operations management. Journal of operations management, 17(1), pp.97-113.

Seider, W.D., Seader, J.D. and Lewin, D.R., 2009. Product & Process Design Principles: Synthesis, Analysis And Evaluation. John Wiley & Sons.

Seuring, S. and Muller, M., 2008. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. Journal of cleaner production, 16(15), pp.1699-1710.

Slack, N., Chambers, S. and Johnston, R., 2010. Operations management. Pearson education.

Stadtler, H., (2005). Supply chain management and advanced planning––basics, overview and challenges. European journal of operational research, 163(3), pp.575-588.

Stadtler, H., 2015. Supply chain management: An overview. In Supply chain management and advanced planning (pp. 3-28). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Stevenson, W.J. and Hojati, M., 2007. Operations management (Vol. 8). Boston: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Stuart, I., McCutcheon, D., Handfield, R., McLachlin, R. and Samson, D. (2002). Effective case research in operations management: a process perspective. Journal of Operations Management, 20(5), pp.419-433.

Teece, D.J., 2010. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long range planning, 43(2), pp.172-194.

meclizine

This blog was… how do you say it? Relevant!! Finally I have found something that helped me. Many thanks!

https://twrd.in/z6ixMPl

cialis cost http://tadalafilise.cyou/# cheap cialis pills for sale

Really informative post.Thanks Again. Awesome.

https://undress.vip/

Great, thanks for sharing this article post.Much thanks again. Want more.

hl6999.com

Thanks so much for the blog.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

https://kobold-ai.com/

Very good article post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

https://milkyway.cs.rpi.edu/milkyway/show_user.php?userid=6265475

This is one awesome post. Keep writing.

https://propertyratesinnagpur22085.blogdigy.com/new-step-by-step-map-for-property-rates-in-nagpur-38381712

Very informative blog article. Really Great.

https://travisdgfpy.widblog.com/79523019/the-fact-about-cricket-updates-ipl-that-no-one-is-suggesting

Im thankful for the blog article. Awesome.

https://trekkingnearbangalore13789.blogthisbiz.com/30415535/the-definitive-guide-to-trekking-near-bangalore

Appreciate you sharing, great blog post.Really thank you! Will read on…

https://lukaskxki32097.actoblog.com/25426275/don-t-get-grounded-a-guide-to-renewing-your-80-97-115-115-112-111-114-116-32

I think this is a real great article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

https://best-packers-and-movers-n45555.dgbloggers.com/25236598/top-best-packers-and-movers-nangal-secrets

Wow, great article.Really looking forward to read more.

https://dungeonborne.com/act/tuc/index.html

I value the blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Will read on…

https://www.landmark.edu/?URL=https://www.mpa17.com/product-category/particle-counter/

Thanks for sharing, this is a fantastic article post.Really thank you! Great.

https://liveplayclub.com/

Muchos Gracias for your article post.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

https://ieconnects.ie.edu/click?r=https://ynews.page.link/ex1LP

Im thankful for the article post.Much thanks again. Want more.

https://pulseersport.com/

Thanks again for the article post.Really thank you! Fantastic.

https://crushon.ai/trends/game

Muchos Gracias for your blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

https://holdenbpdp54320.plpwiki.com/5837350/rishikesh_camping_packages_tips

This is one awesome article.Thanks Again. Awesome.

https://free-chatgpt.ai/

This is one awesome blog post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

https://www.us-machines.com/

A round of applause for your blog article.Thanks Again. Want more.

https://www.us-machines.com/

Thanks for the post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

https://crushon.ai/trends/nsfw_ai

Awesome blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

https://undressai.cc

Major thankies for the article.Really thank you! Really Great.

https://www.panmin.com.es

Hey, thanks for the article. Fantastic.

https://www.paidusolar.com

Looking forward to reading more. Great blog article.Thanks Again. Great.

https://casinoplus.net.ph

Muchos Gracias for your blog post.Really looking forward to read more. Awesome.

https://crushon.ai/character/503eeebe-1626-45bf-89e9-8614106dc5ab/details

Im thankful for the blog article. Great.

https://crushon.ai/

wow, awesome post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

https://crushon.ai/character/f5757531-9a53-4c38-85ef-cd5ae51cdc13/details

Hey, thanks for the blog article.Really thank you! Will read on…

https://aichatting.ai/

Very good post. Really Cool.

https://mygenerator.ai/

Appreciate you sharing, great article post.Really thank you! Want more.

https://www.kubet.fyi/

Major thankies for the article.

https://bonitocase.com/

Enjoyed every bit of your article post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Great.

https://www.oneuedu.com/visa

Major thankies for the article.Much thanks again. Great.

https://casinoplus.net.ph/

Thanks-a-mundo for the article post.Much thanks again.

https://crushon.ai/character/83a80dbc-64e5-4b30-beda-7d42415f68e6/details

I am so grateful for your blog article.Thanks Again.

https://crushon.ai/

wow, awesome blog article.Really thank you! Will read on…

https://crushon.ai/

Very good article post. Much obliged.

https://chat.openai.com/g/g-A2YK8Gob6-pdf-ai-gpt-chat-pdf

I really liked your post.Really looking forward to read more. Cool.

https://crushon.ai/

Really informative blog post.Really thank you! Really Great.

https://zhongli998.com

I cannot thank you enough for the article post. Really Cool.

https://tycent520.com

I appreciate you sharing this blog article.

https://www.zoomesh.us

Really appreciate you sharing this blog post.Really thank you! Much obliged.

https://www.temporaryfencesales.ca

A big thank you for your blog post.Thanks Again. Will read on…

https://www.clearvufence.co.za

Awesome blog.Much thanks again. Cool.

https://animegenerator.ai/

Major thankies for the blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.

https://nsfwgenerator.ai/

Very informative post.Much thanks again. Keep writing.

https://fouadmods.net/

Great, thanks for sharing this article. Want more.

https://chat.openai.com/g/g-0faZCnuDx-devin-ai

Great, thanks for sharing this blog post.Much thanks again. Want more.

https://www.yinraohair.com/human-hair/tape-ins

Very informative blog post. Will read on…

https://www.yinraohair.com/wigs/shop-by-occasion/party

Wow, great article post.Really looking forward to read more. Fantastic.

https://www.burgundywave.com/users/kamshetparagliding

Im obliged for the blog article. Keep writing.

https://felixbpdr65421.wikienlightenment.com/6788369/occupational_english_test

Thank you ever so for you blog article.Really thank you! Really Great.

https://marioxkxi31097.blue-blogs.com/31561263/pvc-o-pipe-manufacturers-in-india

Great, thanks for sharing this post.Thanks Again. Cool.

https://waylonzsjy99875.blogrelation.com/31291623/australia-118-105-115-97-application-tips

Hey, thanks for the blog post. Really Great.

https://jessicav777dlu8.blue-blogs.com/profile

I really like and appreciate your blog article.Really thank you! Keep writing.

https://saxenda-kopen79901.blogolize.com/navigating-the-world-of-pipe-fittings-manufacturers-a-comprehensive-guide-64780854

Thanks for the article. Great.

https://arthurkjfzu.wikidirective.com/6594479/details_fiction_and_disawar_satta_king

Appreciate you sharing, great post.Really thank you! Cool.

https://judahsohx99876.birderswiki.com/516086/stainless_steel_pipe_nipples